People grow more than enough food to feed all people adequately. In 2017-2018, the world grew enough cereal grains to provide adequate food energy for 10 billion to 13 billion people. The world had about 7.6 billion people in 2017. Stocks of cereal grains carried forward from prior harvests reached record highs amid plunging cereal grain prices, showing that the grain supply exceeded demand.

LECTURE

Hunger does not pay

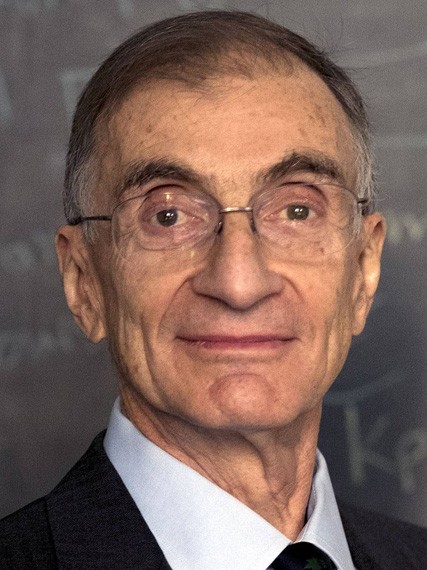

Joel E. Cohen

Series Demography Today 2018/2019

11

MAR

2019

LECTURE

Hunger does not pay

Joel E. Cohen

Series Demography Today 2018/2019

11 MAR 2019

SYNOPSIS

Breakthroughs in agronomic productivity were unprecedented. The dismal paradox is that, in 2017, roughly 800 million people were chronically hungry and 150.8 million children less than 5 years old were stunted from chronic undernutrition (22.2 percent of the 677.9 million children under 5 years of age). Many times more people were chronically hungry than were acutely hungry as a result of famines due to warfare, environmental disruptions, or short-term governmental interventions. In the world market for cereal grains, chronically hungry people exercised less effective demand (demand supported by customers’ orders and capacity to pay) than people who bought the grains to feed animals or for industrial production, or who chose to store it for future sale. As a result, people consumed less than half (42.8 percent) of the cereal grains grown last year. The hunger of those too poor to pay for enough food is economically invisible in current grain markets. But the cumulative effects of childhood stunting from chronic undernutrition lower national income substantially in developing countries. Governments, backed by international economic institutions, should float hunger bonds to patient investors, public and private, to eradicate chronic hunger today in return for a healthier, more productive labor force tomorrow. Purely economic arguments alone justify eradicating chronic hunger. Economic analyses ignore the intrinsic value of fewer children dying young and of fewer surviving brains damaged by hunger. The moral boundaries of markets moved over the past two centuries to exclude slavery. In a world of superabundant food, the moral boundaries of markets should move again to end the assumption and practice that a person’s ability to pay for food determines whether he or she goes hungry.

SPEAKER

Joel E. Cohen

Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of Populations at The Rockefeller University and Columbia University, New York