Assessing Space Exploration’s Spinoffs: How Space Exploration Transformed and Improved Our Lives

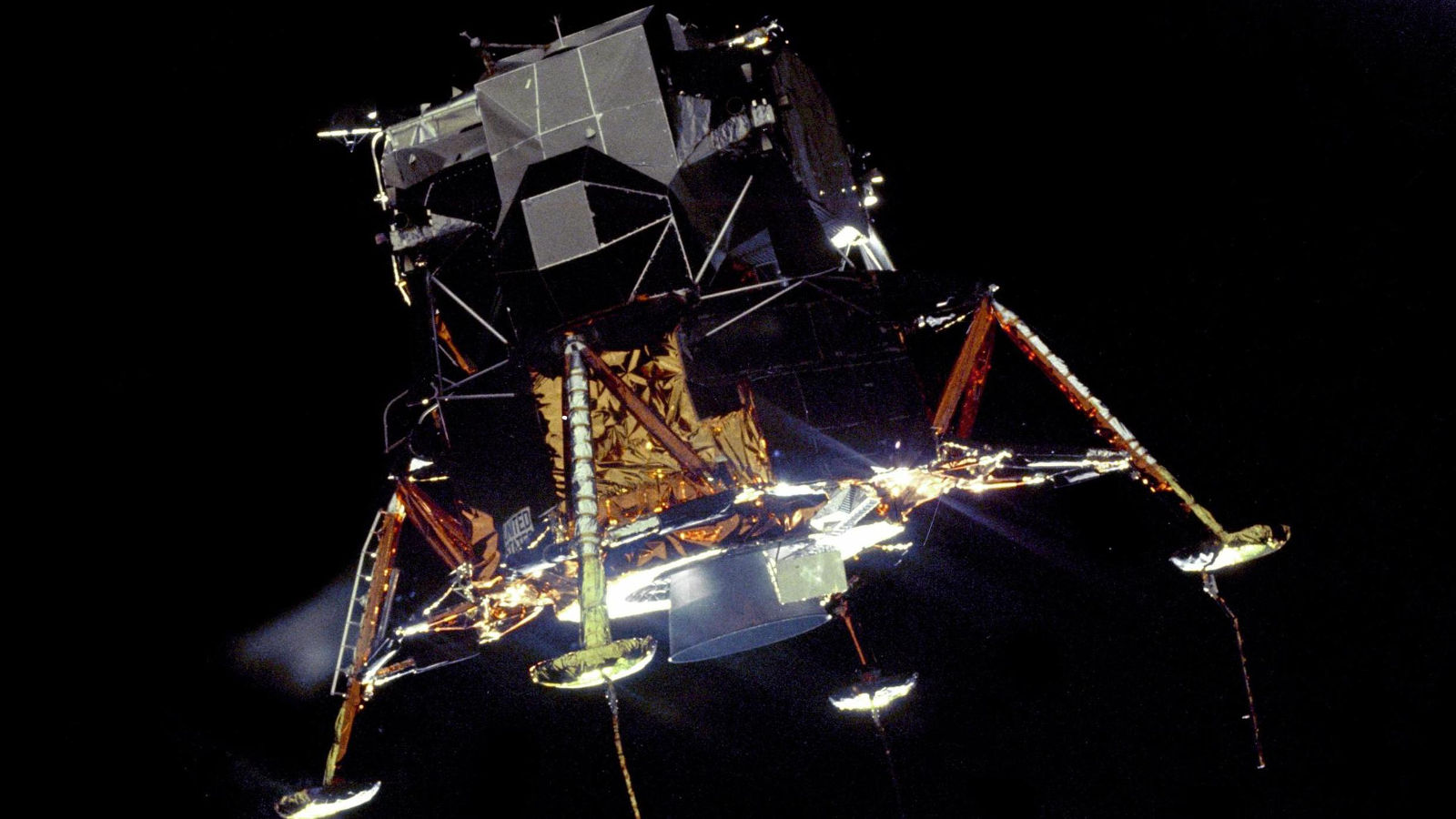

This coming 20th of July will be the 50th anniversary of the “small step for a man” and “giant leap for mankind” which Neil Armstrong took on the surface of the Moon. In commemoration of this historic feat, the BBVA Foundation, in collaboration with Spanish national newspaper El Mundo, presents a special multimedia publication in which four experts analyze the significance of Apollo 11 from different perspectives. In this article, Roger D. Launius – chief historian of NASA, former Associate Director for Collections and Curatorial Affairs of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C., and author of “Apollo’s Legacy” – explores the technological heritage of the space race. From instantaneous global communications and the Internet to smartphones and GPS, space exploration has transformed and improved people’s lives. A video interview with Dr. Launius is also available by clicking on the ‘play’ button on the image at the top of this page.

26 June, 2019

Mostly we hear people mention Tang and Teflon—both of which predate NASA—whenever asked about commercial products that resulted from research and development pursued to support space exploration. This is unfortunate. NASA has changed our existence with its “spinoffs,” commercial products that had at least some of their origins as a result of spaceflight-related research. The space agency has documented the stories behind many of the most spectacular spinoffs, and they range from laser angioplasty to body imaging for medical diagnostics to all manner of data analysis and computer technology. Without question, our lives have been fundamentally altered and enhanced through technologies researched and developed to support the necessities of spaceflight.

To appreciate the magnitude of how technology originating from space research has transformed the human existence ask yourself a counterfactual question: How would your life today be different if we did not fly in space? There can be no fully satisfactory answer to that question since one person’s vision is another’s belly-laugh. But perhaps we can begin with the elimination of global instantaneous telecommunications. Imagine no internet, no easy international calling, no direct television, no up-to-the-minute sporting events or news from other parts of the world, no skyping with friends worldwide, and the list goes on and on.

NASA has spent a lot of time and trouble trying to track these benefits of the space program. With the caveat that technology transfer is an exceptionally complex subject that is almost impossible to track properly, these various studies show an incredible amount of technological lagniappe from the effort to access and operate in space. NASA has documented more than 1,500 technologies that have benefited humanity, improved the quality of life, and helped to advance economic welfare.

An impressive NASA web site, NASA Home & City, features stories of more than 130 spinoffs in a virtual environment, making possible tours through buildings to discover common items that spaceflight inspired or helped improve. This site features commercial products that apply NASA technology originally developed for studying and exploring space that are available around the globe for all to use.

Medical applications

Beyond that, the Apollo program to reach the Moon in the 1960s was responsible for several significant spinoff technologies that have found their way into everyday life. For example, observing the health of astronauts as far away as 240,000 miles prompted NASA to support the development of biomedical monitoring systems that could check vital signs. Those technologies are ubiquitous today, as anyone with a heart condition can attest as sensors keep track of every aspect of the patient’s life signs. As only one specific example of this type of technology, the Medrad Corp. utilized NASA’s Apollo technology to develop a pacemaker to monitor the heart continuously, recognize the onset of ventricular fibrillation, and deliver a corrective electrical shock. The device is used worldwide to preserve the lives of millions of heart patients; it is, in effect, a miniaturized version of the defibrillator used by paramedics and hospitals to restore rhythmic heartbeat after fibrillation but has the unique advantage of being permanently available to the patient at risk.

Additionally, medical imaging technology has roots in the space program. Bone blocks underlying tissue, making it difficult to get clear x-rays of soft body tissues. NASA pioneered the filters for enhancing imagery from space in its Landsat Earth resources satellite, and similar filters were transferred to medical imaging equipment to block out bone and enhance soft tissue images with an optical decoder developed by NASA. This clearer picture of lung and other tissue revolutionized medical imagery in the 1970s.

Thermal clothing and financial transactions

Likewise, clothing to allow astronauts to survive in the extreme environment of space also allow humans to operate in extreme cold on Earth. Comfort Products, Inc., which worked on spacesuit components, adapted some of its technology in the early 1970s to cold weather gloves and thermal boots. The company thermally heated these products in exactly the same way that they did with spacesuits on the Moon. The next time you see outdoor workers in the dead of winter repairing some electrical cable or building a high rise, think of the knowledge gained from space exploration in making their activities more effective.

When shopping at a store, few people recognize that the electronic systems in place for purchases and credit transfers originated with the Apollo program. Aerospace corporation, TRW Inc., applied the Apollo review checkout procedures used to ensure the space vehicles and rockets were ready for flight to retail-store and bank-transaction systems in the early 1970s—as well as to control long-distance financial systems—enabling the current ease of retail purchases. The automatic checkout equipment for Apollo employed one of the most complex computer systems in the world during the 1960s, managing the thousands of separate actions that had to take place before a space vehicle was certified for launch.

Built from scratch at the time, this system required a rapid expansion of computer systems technology and it worked well for the Moon landing effort. Quickly it became apparent that this computer power could be refined and used effectively in commercial settings. Soon TRW convinced financial institutions to adopt the technology and the bank credit system achieved significant improvement in speed and accuracy of transactions, credit authorization, and inventory control. Thereafter, similar computer systems found employment in airlines reservation offices, car rental agencies, hotels, restaurants, shops, and a host of other consumer businesses. No question, the beginnings of this transformation started with Apollo, and has rapidly evolved ever after.

Translation systems and land management

In another instance of advances in computer technology, when NASA began preparations for the for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project flown by astronauts of the United States and cosmonauts of the Soviet Union in 1975 the space agency realized it need large-scale informational exchange with a computerized translation system. NASA contract with the LATSEC Corporation and the World Translation Company of Canada to develop a machine translation system known as SYSTRAN II. This system increased the output of a human translator by five to eight times, affording cost savings by allowing a large increase in document production without hiring additional people. Extra savings also accrued from automatic production of camera-ready copy. NASA employed this system to translate service manuals, studies, catalogs, list of parts, textbooks, technical reports, education/training materials and myriad other materials from Russian to English, and vice versa. System is operational for six language pairs. This jump-started computer translation that has become ubiquitous in the years since.

As a final example, when NASA launched its Landsat satellite in 1972 it made possible the systematic analysis of land use over a long period of time. Land resource management of farmland transformed the agriculture industry worldwide by allowing farmers to understand how their patterns of usage could be enhanced with data from space. The same was true of city land usage. Essentially, images of city streets from space helped transportation, housing, electrical grid, and other planners in transforming the cityscape. It has become an indispensable tool for cities around the globe since first introduced more than 45 years ago.

Smartphones, telecommunications, and GPS

The results of these investments in space technology are everywhere around us. The miniature electronics technologies developed for spaceflight found their way into the many devices we use today, such as today’s smartphones. It is from the space program’s investment in computing and telecommunications technology that the Internet emerged. It was from space R&D that our dominant system of navigation—the Global Positioning System (GPS)—has made reading a paper map obsolete. These are only a few examples among many hundreds that might be offered.

Whether good or bad, no amount of cost-benefit analysis, which the spinoff argument essentially makes, can completely justify NASA’s activities. But try to envision a world in which spaceflight did not exist. There is no doubt but that many pervasive technologies would either have never been invented or would not have reached everyday use as quickly as they did. The point, of course, is that the past did not have to develop in the way that it did, and that there is ample evidence to suggest that the space program pushed technological development in certain paths that might have not been followed otherwise.

Think of the many high technology capabilities we enjoy—starting with biomedical diagnostics and related technologies and ending with computing breakthroughs—that might well have followed different courses and perhaps have lagged beyond their present breakneck pace as a result. Some of us might well think that a positive development, though I doubt most would want to go back to typewriters, problematic global communication, and the manner in which we lived our lives before the space age. Despite the nostalgia for bygone eras before the information and technology revolution coming in the last half of the twentieth century—found in such popular television shows as Downton Abbey and Mad Men—I believe few would like to return that time. I certainly wouldn’t. I remember what a remarkable experience it was to watch the opening of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics via satellite in real time. It is no longer a remarkable occurrence; we have come to accept it as the norm and I have no wish to return to a pre-spaceflight era.

What might the future hold? One thing is for certain, pushing technological research and development to advance the technology of spaceflight will also push the technology available for everyday use.